A teenager, I awoke abruptly from my Shabbos nap to my older sister, who was visiting from out of town, standing over me. “We’re ordering Chinese food now, what are you having?” Half asleep (and also not wishing to eat treif Chinese food), I replied, “Oh, I’m ok, I don’t think I’m going to eat until later. Don’t worry about me. I’ll sit with you when it arrives.” “You’re a witch!” came her booming response, as she stormed out and slammed my bedroom door. Out in the living room I heard, “Your daughter doesn’t want to be part of the family!”

As a clinician, it is not too often that my baal teshuva clients come in with their BT experience as part of what they came to therapy to discuss. They look at me with surprise when I want to spend some time on that aspect of their life during my evaluation. “How much of your family is frum? How much support did you get? What’s it like visiting their homes these days? How does it feel at holiday time?” More often than not, I see a shrug; “it is what it is.” I personally have never seen an article published anywhere about a persons BT journey. That doesn’t mean they don’t exist, but I just wonder often, how come such a BIG life experience does not have a BIG presence in peoples life discussions?

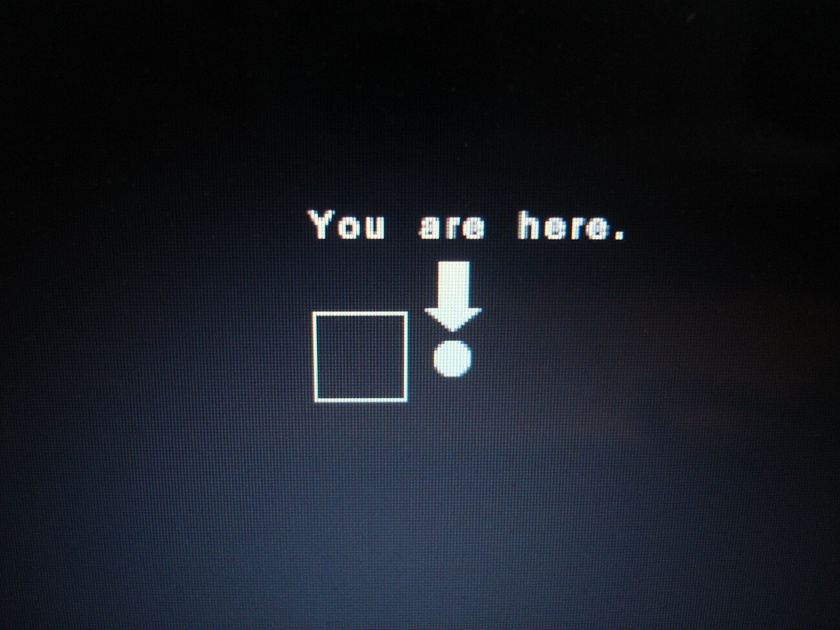

Every Baal Teshuva has their unique individual experience of becoming frum, be it together with their family, by themself, with one or two family members, with guidance or without, with support, without support, with silent acceptance, with outright rejection. I climbed the ladder alone. As my family smeared the rungs with grease, Hashem lovingly wiped them and hoisted me up.

Here’s my story:

Unlike many Baalei Teshuva, I had the benefit of a Day School education. I often get asked why an anti-frum family would send their child to Day School. My answers: it was up the block, it dismissed late in the day, it had bussing, and my parents didn’t want their children to be completely unafilliated. But memorizing a bunch of facts about holidays does not take a child very far with no reference point in the home.

I grew up in isolation. The only child in a dark home on an acre of wooded land, set far back from the road, with no other kids on the block and no frum kids for miles. My parents, professionals, worked until late at night. But I did have G-D. That’s who I talked to, cried to, pleaded with, explained my feelings to. What I wanted more than anything in the world as a child, was to be part of something. I would sleep over at friends’ houses for Shabbos, and watch longingly, starvingly, as kids darted in and out of eachothers’ houses. The Young Israel my friends went to was, to my mind, heaven on earth. Hoards of kids, hustle and bustle and entertainment. Candy. Prizes. I came to realize that my friends were not alone in their homes or on their blocks. I promised myself that when I grew up, I would be part of something. I dreamed of living close to the street, where I could hear the neighborhood kids. I dreamed of being a Bnos mom, a PTA mom, a class trip chaperone, driving a station wagon (what we had back in the olden days before mini vans).

In my home, we “celebrated Shabbat” with frozen Kineret challah and Malaga wine. My father stumbled through Kiddish in his broken Hebrew. Pesach prep involved washing down the kitchen only, and taking out the Pesach dishes. My mother would take a penny from the maid and tape it to the fridge. I had no idea until I was married that the entire house had to be cleaned. Nor had I heard of a chometz sales document. We also had a sukkah. It was a permanent arbor at the side of the house. The sechach was the grapevines growing over it, which we detached with a snip. The overall attitude in my home was “what’s important is to be a good person. The rituals are for people with OCD, and G-D doesn’t care about rituals anyway.”

I have to admit that as a child, I considered myself very lucky to be able to celebrate so many holidays and get so many gifts: Chanuka gifts, gifts from Santa, Simchas Torah candy and Halloween and Valentines candy. The belief was that we are Americans, and part of being American was celebrating whatever was being celebrated across America. And so… we had a small Xmas tree and long socks hanging by the fireplace…in view of the Menorah. I would go to school gushing over my fun Halloween night and my visit from Santa. I got yelled at, teased and tormented for this, and didn’t understand. My family wore green on St. Patrick’s day, and that’s what I’d wear to school. My Jewish school. My parents didn’t even think to protect me from the fallout by warning me not to talk about these practices. It didn’t occur to them that they were setting their child up to be the laughing stock of the school; peers and teachers alike.

One weekend, I slept over at my father’s secretary’s house because my parents went away. Their daughter was a playmate of mine. They were Catholic. Sunday morning arrived, and I called my mother to tell her they were headed to church so I needed a pickup. My mother instructed me that there is nothing wrong with going to church with them, it will be an educational experience for me…just don’t bow or eat the cracker the priest gives out. Imagine my embarrassment when the 200 people got down on their knees for an extended prayer, and there I stood… I was ten years old.

When I graduated 8th grade, my parents forced me to go to public school, “to get a well-rounded education.” I was bullied, had lit matches thrown at me, got spit on, and was attacked verbally for taking Jewish holidays off. This was the same school where my older brother had been mugged at knifepoint and then had a huge swastika spray painted on our block above the words “dirty Jew.” But somehow sending me there was crucial. So I could be “well-rounded.”

At the end of the year, I begged to be sent back to Day School to be with my friends. I was told, “we’re not spending all the money for you to be the only kid in the grade who isn’t religious!” As if that was my doing. “Fine” I replied. “Saturday I’ll be at shul.” My mother tagged along as I stomped up the road. It was a jeans-and-khakis affair of about ten couples, the gabbai was intermarried and the rabbi took his kids swimming after Shabbos lunch. I went every week, and so did she.

My first feelings of D’veikus were like the most intense kind of falling in love. It was exciting, serene, intimate, deeply moving. I was floating. I wanted to show my gratitude for this Presence. I began to follow some of the halachos… and that’s where the war of the wills began.

I’d tape my bathroom light on. Someone would untape it and close the light. The bathroom was black tile with no window. I’d tape the fridge light. Midday Shabbos I’d open the fridge for a drink and find the light on. Now I couldn’t close the door. So I’d leave it open. And get yelled at. I’d leave the AC on in my bedroom. I’d go in for bed and find it off. I’d check the hechsher on the new salad dressing before pouring it. I’d be told I was crazy, salad dressing doesn’t need to be kosher. I’d wash the dishes Friday night in cold water with no sponge. I’d be told I wasn’t honoring my mother by properly washing the dishes. I’d want to stay home Saturday afternoon when they got into the car to eat dinner out. I’d be told I’m causing pain by not wanting to spend time with my parents.

When I got married and became part of a frum community, I realized I had been eating bishul akum at home and treif dairy in restaurants, never ate the shiur of anything at the seder (actually our seders were 5pm, so it wasn’t even Pesach!), had never sat in a kosher Sukkah… never mind the bit about avodah zara! That first year, I dreaded every holiday, where I would find out what K’halacha really looked like, and grieve some more.

When I put on long sleeves and a sheitel, bedlam broke loose on my family’s side. When I showed up at my parents’ house in a tichel, I was told to get the rag off my head because I looked like Aunt Jemima. If I was seen davening, I was told, “All the praying in the world won’t make you a good person. This isn’t what G-D wants from you.”

Each time something upsetting happens in my life, it is attributed by my family to my being frum. I’m still unclear on how that math works.

Hashem blessed me with a sense of humor, and the ability to laugh at myself. Without that, being a new kallah trying to keep a frum home would have been unbearably embarrassing. Our first Pesach, we went to the kosher supermarket and I began to load the cart. I knew what to get: Manischewitz coffee cake mix, Rokeach egg kichels, Streits matzohs in the pink box. I turned back and found the cart empty! My husband had been putting each item back on the shelf as I went. “Gebrokts.” He said. “huh???” That was my introduction to the Heimishe Hechsher. I could buy any item in the store with those markings. Ok. No problem. I cleaned the kitchen, put away the appliances, and went out back to get a rock. “Ok, I’m ready for you to kasher the kiddish cup!” I said, beaming and handing him the teapot.

“Uh… why’s there a boulder in the kitchen sink?”

“kashering stone!”

“what…do you want me to do?” He asked with a straight face.

“You put the kiddish cup in the sink with the stone, you pour the hot water over them both, and it makes it Peisadik. Duh!” “

“So let me make sure I understand. You put a rock from the yard in a chometzdik sink with the kiddish cup, then you pour hot water from the chometz teapot over the two… and now it’s all Peisadik? And then what do we do with the rock???”

I stood there, jaw open. Speechless.

“Is this what your mother did for Pesach?”

My eyes filled with tears, as I nodded.

Once, at a visit to my parents, my husband stood over a potted plant filled with utensils, scratching his chin.

“Why does the plant have forks jutting out of it?”

I looked at him as if he had just landed here from Mars. “They got treifed up, so they go in the plant!”

“I see. And uh, how long do they stay in the plant?”

“Like, ten weeks I think.”

“Ten weeks, you say. And then what happens?”

“Well then they’re kosher again. Duh!”

When he was done laughing, my husband taught me the correct way to deal with misused utensils.

I had never seen cholov yisroel, shemurah matza, an oil menorah, mayim achronim, esrogim saved rather than tossed in the trash… and when I was introduced to my first keilim mikvah, I took my mothers entire utensil drawer out back to the waterfront behind their house and began dunking it all off the edge of the dock. Let’s not get into what happened when she found out…

The stories are endless, and I can laugh about it now. But for me, when I think of how I was robbed of the opportunity to follow Hashem’s laws for over two decades of my life, I hurt. I hear the words of Yom Kippur Mussaf “Halo Mishma Ozen Daveh Libeinu…”

I get told a lot that my family is considered a tinok shenishba. It’s not my place to determine if that is so or if it isn’t. It’s my place to honor how it felt to me to be actively denied the opportunity to be frum. Many clients come in with stories of being denied certain nonreligious freedoms, but how many have an untold story of being denied the ability to be religious? What are the possible feelings that some baalei teshuva who made the journey unsupported may feel and keep to themselves? I feel obligated to use my experience to further open this dialogue.

Nobody took me under their wing and taught me how to observe mitzvos. I didn’t go to a seminary or an institute. I racked my brain to recall what I had been quizzed on in school, and read many books. I read some Rambam. I didn’t even know what to read. I just bought books and devoured them and followed what it said inside. I googled things. I copied what I saw my friends do. I attend shiurim. I’m still learning. I tell myself we all are.

One day, my neighbor across the street said to me sternly, “I think it’s time to start seeing your friends as your frum family, the frum family you always wanted.” It was a turning point for me, a moment I stopped “undoing” and started living.

I recently attended Pesach seder out of town with the family of my second husband, a brand new BT. It was a jeans and cell phones affair which I sat through with a smile glued to my face and a heart heavy with painful memories as 27 people shifted in their seats and checked their watches. I asked Hashem why He could possibly want me back at square one. Hadn’t I earned a kosher, religious Pesach evermore?!

At the local Chabad the next morning, the Rabbi asked in his drasha, “Why do we stop at “v’lakachti, Hashem making us a nation, which occurs at Sinai? What about that fifth act of redemption, whereby Hashem settles us in the Promised Land?” No, he explained. Hashem doesn’t do that part FOR us. Equipped with the freedom, the identity and the laws, we have to figure out how to settle ourselves.

He added, firmly, “Just because you set out to do a mitzvah, and you learned to do a mitzvah, and you wish to do a mitzvah, that doesn’t mean you have it coming to you! Don’t assume entitlement!” My ears rang.

On the second day the Rabbi added, “Don’t put on those ridiculous goggles to eat the marror! Life is not a journey away from pain, but a journey through pain. That’s why we make a bracha on the bitter herbs!” Isn’t that what I teach my clients in DBT? Distress tolerance? And yet I’m not on board with that goal when it comes to my religious life. I want the walk through the desert to be over. The evolution to be complete. But it’s not. So what that says to me is that my BT journey is always a relevant topic of therapeutic discussion for me. And probably for a lot of other BT’s, if given the forum and opportunity.

So, 25 years frum, I enter a new, unexpected, deeply rattling chapter of my religious journey, not dissimilar to what my ancestors have experienced since entering the Promised Land. I guess I’ll work on getting settled.

Previous

Previous